When I put this book down, what stayed with me most wasn’t anger — it was forgiveness. Not in the abstract, not in the way it’s usually presented as something noble or aspirational, but in the way it actually exists when it’s hard, undeserved, and deeply human.

This story made me question the small, stubborn things we hold against one another. The quiet power struggles. The need to be right. The desire to feel justified, or in control, when we’ve been wronged. I found myself asking why we cling so tightly to those things — and what it would really take to let them go.

Because here, forgiveness wasn’t theoretical. It was practiced.

Ronald’s ability to forgive stood out to me in a way I didn’t expect. To look at something so devastating and say: this was a mistake, rather than allowing it to calcify into resentment — that requires a kind of strength I’m not sure most of us ever have to test. It would have been understandable if he couldn’t. And yet, he did.

And then there was Jennifer.

What struck me just as deeply was her willingness to admit she was wrong — not to dig in, not to protect herself through denial, not to cling to a version of events simply because it had once been hers. To own the truth once it became clear, even when that truth dismantled everything she thought she knew about her own experience, takes an extraordinary amount of integrity.

This book changed the way I think about certainty.

It forced me to accept, on a much deeper level, that no matter how convinced we are of our own truth, that truth may not be as accurate as we believe. I recently read about how memory actually works — that over time, we don’t remember the event itself, but our memory of the event. Then our memory of that memory. And then the memory of that memory. Each recall subtly reshapes the original until what we’re holding is no longer the event, but a reconstruction influenced by time, emotion, and interpretation.

It’s like a game of telephone. Each retelling replaces the last, until the final message bears only fragments of the original reality.

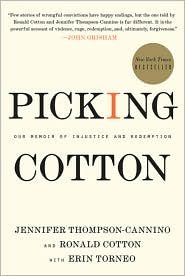

Reading Picking Cotton through that lens was unsettling. It made me realize how fragile certainty can be — and how dangerous it is to treat it as infallible.

At the same time, this book made me profoundly grateful for science. For the advancements that allow us to stop people from spending years — entire lives — behind bars for crimes they didn’t commit. There was a quiet relief in knowing that progress exists, even if it arrived too late for some.

As for belief — this book complicated that question for me.

It did make me think about how often women are not believed, but not in the way I expected. What I felt most strongly was pride. Pride that a woman stood for what she knew to be true. That she advocated for herself, for her mental health, for justice, and for other women who could have been harmed after her. That she put her trauma into the public eye not for sympathy, but because she believed it mattered.

It is heartbreaking that a man lost eleven years of his life for something he didn’t do. Nothing diminishes that.

But acknowledging that doesn’t erase Jennifer’s bravery. She may have been wrong about who hurt her — but she was not wrong that she was hurt.

And that distinction matters.

When this book closed, I was left sitting with the uncomfortable truth that forgiveness, accountability, and justice don’t always arrive cleanly or in perfect alignment. Sometimes they exist together, imperfectly. Sometimes they ask more of us than certainty ever could.

This isn’t a story that offers easy conclusions. It asks instead for humility — about memory, about truth, and about the courage it takes to admit when what we believed no longer holds.

And maybe that’s the hardest kind of forgiveness there is.

Leave a comment